THE FIRST TIME I SAW Mulholland Drive was in 2002 while I was visiting Los Angeles for pilot season. My friend’s aunt, whom I didn’t know until that night, had invited me to join her at the Vista Theatre on Sunset. The movie left me utterly discombobulated. It perplexed and disturbed me in equal measure, so much so that I actually felt dizzy. Everything outside looked sinister or compromised. The man smoking a cigarette by the lamppost, what did he know about me? Was that terrifying, filthy bum in the movie lurking in the alleyway behind the theater dumpster? Why did everything around me seem so dark and yet vivid all of a sudden?

My friend’s aunt had kindly reserved a table for us at Jones Hollywood Cafe, but I could barely pay attention to my meal or her. I focused on another booth, a man in his sixties with a pretty woman in her twenties, the orange light engraving the deep lines in his face and accentuating the glow of youth on hers. When he laughed, I could see his big, white teeth, and they seemed ready to devour her. She reminded me of Betty, the ingenue played by Naomi Watts in Act I of the movie, impressionable and hopeful. If I moved out to Los Angeles to pursue my own acting dreams, would I end up like Diane Selwyn—Betty’s alter ego in Act II—bitter and broken? Was the filmmaker sending me a dark-blue key but warning me not to use it to open that Pandora’s box?

Such is the power of Mulholland Drive, which I revisited this week when I heard the sad news of director David Lynch’s passing after being evacuated from his home during the recent wildfires. Even though the first time I found the film confounding, it left an indelible impression on me, and its mysterious and ominous allure lingered. Whenever I rewatch Mulholland Drive—as I have many times over the years—its meanings bloom and deepen. I now find it, strangely, to be one of Lynch’s most straightforward stories. In the vein of the Brothers Grimm, Mulholland Drive is a dark, perverse fairytale about Los Angeles: the fantasy of Hollywood stardom, the gritty underside of show business, and the liminal space where the two blur together.

As Lynch put it in Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity:

I love Los Angeles. . . . The golden age of cinema is still alive there, in the smell of jasmine at night and the beautiful weather. And the light is inspiring and energizing. . . . It fills me with the feeling that possibilities are available. . . . It was the light that brought everybody to L.A. to make films in the early days. It’s still a beautiful place.

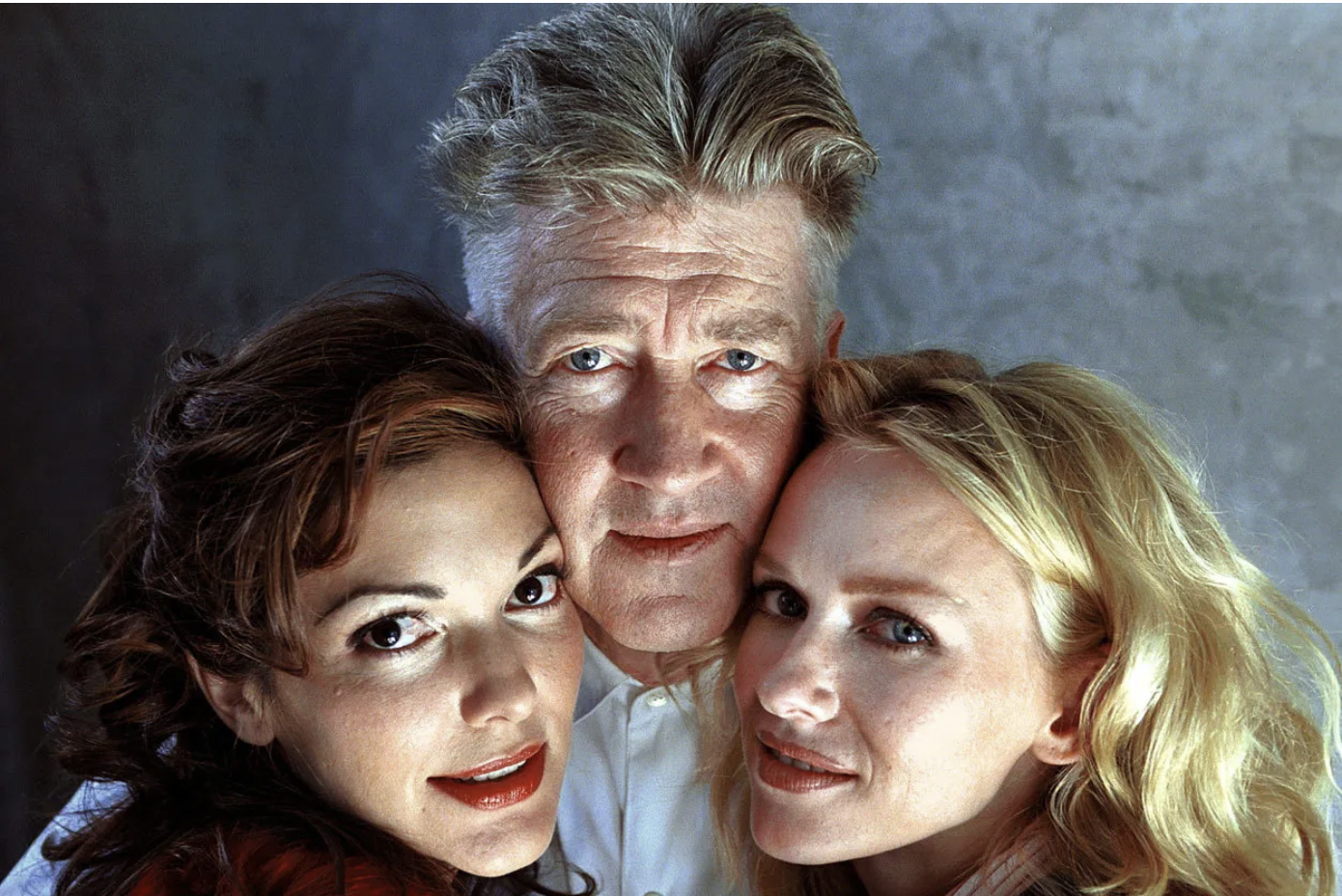

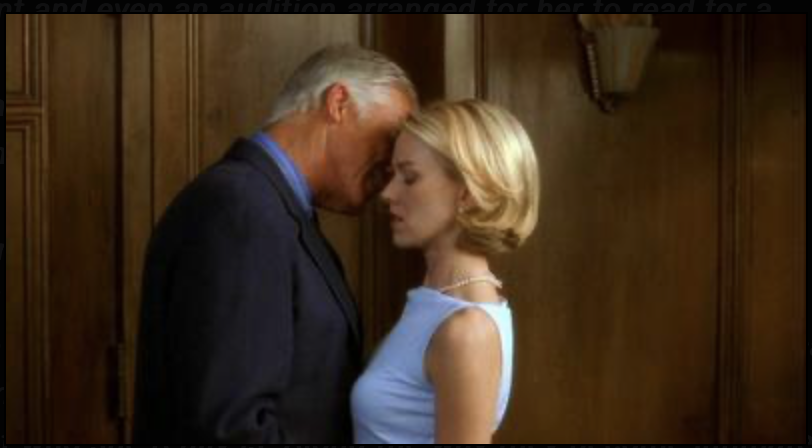

The dream for the golden age of cinema is the Act I of Mulholland Drive. In my mind, it is the fantasy portion of the movie. Personified by bright-blonde “Betty” —an old-fashioned name harkening back to Bette Davis (highbrow), or Betty from the Archie comics (lowbrow)—Naomi Watts comes out to Hollywood with stars in her eyes. In the way Lynch chooses to light and shoot her, she literally glows with optimism. She wears opalescent nail polish and a bright pink sweater with rhinestones so that when she moves, she gleams and glitters. Watts’s performance is so stylized that while I was watching the film the first time I couldn’t believe how syrupy she was. That is until she went into her “big break” audition scene, when all of a sudden she transformed from a wide-eyed innocent into a seductress, fully in control of her scene partner, a seasoned, slick George Hamilton-type, old enough to be her father. I realized it was Lynch’s and Watts’s plan all along to make Betty naïve, perky and over the top in order to stun the viewer in that gritty, sexualized audition scene. A star is born.

The post-audition Betty also is fully in control of “Rita” (Laura Harring), the mysterious, dark-haired bombshell who wanders away from a deadly car wreck and an assassination attempt on Mulholland Drive without any memory of who she is. Betty is Rita’s heroine, helping the damsel in distress piece together her true identity and protecting her from the dark forces pursuing her. The more Rita depends on Betty, the more they are drawn to each other, and in one of the most tender and sensual scenes I’ve ever seen on film, Betty invites Rita into her bed and seduces her while saying “I am in love with you,” over and over like an incantation. It’s as if Cinderella and Snow White became lovers. They merge into one as they kiss. This time when I watched the scene, there is a shot I am convinced is Lynch’s homage to Persona, where Rita’s profile merges with Betty’s full face.

ACT II OF MULHOLLAND DRIVE is the “reality” section of the movie. Watts is no longer the upbeat starlet Betty but rather Diane Selwyn, a jaded, hard-bitten actress pining for Harring, who is now Camilla Rhodes, a glamorous actress on the rise who is leaving her ex-lover Diane far behind in her quest for fame. Diane is the dependent one in this role. She is talentless and whatever acting jobs she’s gotten have been tossed her way by Camilla. She fantasizes about their time together before Camilla ditched her for a famous director, Adam Kesher (Justin Theroux). The warm remembrances of their lovemaking are gone. All that is left is raw sex and obsession. While Camilla still glows, Diane looks tough and hardened and drained of color. She is shabby in her worn-out bathrobe. She sleeps late into the day, wears no makeup, and her hair is jagged and dirty. Lynch shoots her in a harsh light. She seems to have suddenly developed lines in her face.

Every time I watch Naomi Watts’s performance here, I am struck by how brave it is. Her masturbation scene is so raw and painful in its vulnerability that I have a hard time watching it. David Lynch must have inspired so much trust in his actress that she felt safe to express herself with such literal and metaphorical nakedness. I am in awe of him and her.

Whereas the first part of the movie is about the myth of Hollywood, the second part is about its dark, sleazy underbelly. Camilla torments Diane professionally and personally, and Diane’s love devolves into jealousy and hatred. She becomes a bit player in Camilla’s life, both on camera and off. The film’s glamorous Hollywood Regency design in Act I is replaced in Act II by Diane’s slovenly apartment, a flat, painted set background on a soundstage, and Adam’s harsh, angular, modern house in the Hollywood Hills. Instead of being pursued by ominous, enigmatic mobsters, all that’s threatening Diane in the second part of the movie are her poisonous thoughts. And when the hitman Diane hires leaves the blue key on her coffee table signaling that he has successfully completed his task (a basic blue house key compared to the sparkly cobalt, stylized key Rita finds in her purse) she is consumed by agony and guilt for killing her former lover. The old couple whom Betty met on her flight from her hometown to LAX, have now mutated into demons who crawl out from the mysterious blue box held by a dark, hideous bum behind the dumpster, and chase Diane until she shoots herself in the mouth. Diane’s Hollywood dream ends up a seedy, sordid nightmare. The rawest of neo-noirs.

What unites the two sections is that the film begins and ends at night atop Mulholland Drive, a physical and psychological threshold between fantasy and reality. It’s where the Hollywood Hills also begin and end. And so David Lynch makes it the locus: where Camilla is killed off (whether literally or metaphorically, depending of one’s interpretation) and “Rita” is born. Knowing Lynch’s dedication to Transcendental Meditation and his belief that the spirit can never be destroyed, I think he intends Mulholland Drive to be the place where this transition from life to death, from corporeality to make-believe and back again, happens.

A spontaneous offrenda, of sorts, left at Bob’s Big Boy, one of David Lynch’s favorite local spots for a cup of coffee and a slice of pie.

IT’S NO SURPRISE TO ME that David Lynch actually lived in a blue house that veered off this infamous road. Los Angeles, represented by Mulholland Drive, is a dark path, full of twists and turns and peril. We have sadly seen this the last few weeks in the devastation of the L.A. wildfires. But the glittering lights down below in Hollywood are omnipresent.

Mulholland Drive is David Lynch’s twisted love letter to L.A. In his view, you can’t have light without the darkness, you can’t have joy without pain. And recently, watching helplessly as neighborhoods were consumed by fire, I realized I love this place more than I’d thought. As a formerly reluctant transplant and a struggling actress with big dreams myself, I now willingly call it my home. Los Angeles opens up its sensuousness to its pioneering inhabitants like the night-blooming jasmine at midnight. Angelenos just have to appreciate its particular complexity, mystery and contradiction the way Lynch did. As a director famously beloved by his actors and coworkers, and to whom many owe their illustrious careers, David Lynch became a legendary part of the Dream Factory that drew so many people, himself included, out to Hollywood in the first place. His energy will linger on in the Los Angeles light he loved so much.